Hedonomics: On Subtle Yet Significant Determinants of Happiness

Citation

Tu, Y., & Hsee, C. K. (2018). Hedonomics: On subtle yet significant determinants of happiness. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being . Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers. DOI:nobascholar.com

Open this chapter in the original PDF (exact figure/table layout)

Abstract

One way to pursue happiness is to improve the objective levels of external outcomes such as wealth; that is an economic approach. Another way to pursue happiness is to improve the arrangement of and choices among external outcomes without substantively altering their objective levels; that is a hedonomic approach. This chapter reviews research adopting the latter approach. Specifically, we present a list of subtle yet significant determinants of happiness from four aspects: (1) pattern of consumption, (2) procedure of consumption, (3) (mis)match between the choice phase and the consumption phase, and (4) type of consumption. Although far from comprehensive, these factors offer implications for “choice architects” – government, companies, and individual consumers – on improving happiness

It is almost truism to say that happiness is the ultimate pursuit – or, at least, one of the ultimate pursuits - of life. Hence, “formulas” for improving happiness have always been of interest not only to academics (Diener & Seligman, 2004; Gilbert, 2006; Huppert, Baylis, & Keverne, 2005; Seligman, 2002; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), but also to policy makers and individuals. Intuitively, happiness is correlated with wealth - people in affluent countries are happier than those in poor countries, and people with higher annual income are happier than those with lower annual income, presumably because wealthier individuals have access to more and better material goods (e.g., more and tastier food, larger and better houses, appliances and technologies that liberate them from labor). Indeed, research generally finds a reliable positive link between wealth and happiness (Diener & Oishi, 2000; Lucas & Schimmack, 2009). Yet, the impact of wealth on happiness has its boundaries – their relationship follows a concave curve, such that an increase in wealth will cease to increase experienced happiness in daily life once wealth reaches a certain point (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002; Kahneman & Deaton, 2010).

Then, are there non-economic approaches to increase daily affective well-being, in particular in affluent societies where people already possess and consume a large quantity of external resources? In this chapter, we review research on hedonomics (Hsee, Hastie, & Chen, 2008), which studies how to increase happiness by improving the arrangement of and choices among external outcomes without substantively increasing the objective levels of the external resources. Hedonomics involve many factors. In this chapter, we focus on four examples: (1) the pattern of consumption, (2) the procedure of consumption, (3) the (mis)match between the choice phase and the consumption phase, and (4) the type of consumption. We also explain the corresponding psychological underpinnings. These factors seem subtle, but can produce significant impacts on happiness.

We should note that “happiness” has different meanings, and that in this chapter we focus on only one type of happiness—valenced (positive or negative) hedonic experiences with external stimuli. We do not study specific emotions such as anger and excitement; nor do we study overall life satisfaction or meaning in life.

Pattern of Consumption

A fixed amount of consumption resources can be divided into several chunks and consumed sequentially on separate occasions. The characteristics of these chunks, including the number of chunks, the size of each chunk in the sequence, and the changes in the sizes of chunks, can influence happiness. Segregation of Gains: Segregating a Fixed Amount of Consumption Resources into Several Small Chunks Can Lead to Greater Happiness

Prospect Theory’s value function (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) posits that subjective utility derived from gains follows a concave curve, with diminishing marginal utility. Therefore, for a large quantity of consumption resources, dividing them into a few chunks and treating them as distinct consumption units can take advantage of the steep gain of happiness from “zero consumption” to “some consumption” (i.e., the region close to the reference point) and increase happiness. Indeed, segregating gains is one of the four hedonic editing rules Thaler (1985) formally proposed. It suggests that, for example, a person who plans to eat in a fancy restaurant and get a relaxing massage should arrange these two activities on separate days rather than on the same day, in order to derive greater overall happiness from these two activities. Similarly, a person who receives a notification that a new season of her favorite sitcom is available on Netflix should spread her viewing experience over two weeks, rather than binge-watching all the episodes in two days, in order to maximize the overall pleasure obtained from watching the entire season.

Note that usually segregation inevitably means introducing non-consumption periods into the consumption sequence and lengthening the overall consumption duration. This way, people have more time to recover from satiation or hedonic adaption (see “ Adding Delays” and “ Adding Interruptions and Slowing Down” in this chapter for more information), in addition to taking advantage of the high marginal utility of a small portion of consumption resources. Then, will the segregation principle be effective above and beyond the satiation account, when the total length of consumption is held constant? Redden (2007) offers supporting evidence by merely having participants mentally segregate their consumption (i.e., a manipulation of perceived segregation). In one study, participants ate several jelly beans of different flavors. They either sorted these jelly beans into one broad category (i.e., jelly beans) and treated their eating experience as one unit, or sorted the same amount of jelly beans into several specific categories (e.g., orange jelly beans, banana jelly beans) and treated their experience as a combination of several distinct units. Redden (2007) found that participants reported greater happiness over the course of eating jelly beans in the latter condition, when their eating experience was only mentally segregated and the total duration of consumption is fixed. Improving Sequence: Arranging Chunks of Consumption Resources of Different Sizes in an Ascending Order Can Lead to Greater Happiness

Without doubt, people desire a happy ending, but do they prefer a happy ending at the cost of inferior experiences early in the sequence? Loewenstein and Prelec (1993) find that, holding the objective amount or value of consumption resources constant, people prefer a course during which the quality of experience gets better and better, compared with when the quality of experience remains the same or when the quality of experience gets worse and worse. In one study, when scheduling a dinner at a fancy French restaurant and a dinner at a local Greek restaurant, people preferred the “Greek first French second” sequence over the “French first Greek second” sequence. In a similar vein, Prelec and Loewenstein (1998) show that people preferred the decoupling of payment and consumption, willing to incur losses (e.g., payment) before gains (e.g., consumption experience). Outside the lab, panel data on British employees’ wage change and well-being also provides support to this principle (Clark, 1999) - employees who experienced a positive wage change were happier and more satisfied with their job, regardless of the absolute amount of salary. To illustrate in a stylized way, the annual income stream “$50k, $60k and $70k” generated greater overall happiness than the stream “$60k, $60k, and $60k” or the stream “$70k, $60k, and $50k.”

Noticeably, this preference runs against the economically rational solution based on calculating the present value of a flow of future values via discounting. Specifically, because both future gains and future losses “deflate” in value when evaluated at the present, expediting future gains (to increase their present utility) and postponing future losses (to decrease their present disutility) can maximize the present value of the consumption flow. Nevertheless, this economically optimal arrangement is sub-optimal for happiness. Accelerated Increase ( Velocity of Positive Change): Arranging Chunks of Consumption Resources of Different Sizes in an Acceleratedly Increasing Pattern Can Lead to Greater Happiness

Not only are people sensitive to the change of the sizes of the consumption chunks, as reviewed in “Improving Sequence,” but also they are sensitive to the velocity of the change (Hsee & Abelson, 1991). Specifically, a sequence of consumption resources that increase in quantity or value faster and faster will generate greater happiness than does a sequence of consumption resources that increase in quantity or value at a constant rate (Hsee, Salovey, & Abelson, 1994). For example, a video game player will be happier and more motivated to continue to play the game if the score on the game increases in an accelerating pattern (e.g., 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320,….) than if it increases in a uniform pattern (e.g., 100, 200, 300, 400, …), and this is true even if the score does not correspond to any external rewards and is spurious (Shen & Hsee, 2017).

Procedure of Consumption

The same amount of consumption resources can be consumed in different ways. The characteristics of the procedure – delays, interruptions, speed, and curiosity towards the experience – influence overall happiness.

Adding Delays: Delaying Consumption Can Increase Overall Happiness

Obviously people get pleasure from their moment-to-moment experiences with the consumption stimuli, but can they get pleasure outside the consumption phase? Research shows that, by imagining positive experiences prior to the occurrence, people can get anticipated utility or savoring value (Kahneman, 1999) too. It follows that delaying consumption can generate additional “free” happiness. Indeed, in one study, participants either waited 30 minutes before eating two chocolate candies or ate them immediately, and those who waited reported greater overall enjoyment of the chocolate candies (Nowlis, Mandel, & McCabe, 2004). Therefore this principle suggests that, for example, families should book vacations in advance and online shoppers should not select expedited shipping (especially when it costs extra) to get higher overall enjoyment.

Despite evidence that an externally imposed delay can produce a hedonic boost, do people choose to delay consumption? It is possible that, because waiting requires self-control and people tend to act on impulsive desires immediately (Frederick, Loewenstein, & O’Donoghue, 2002; Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989), people may not opt for it when given the choice. However a few studies documented that, at least in some contexts, people can choose optimally. For example, Loewenstein (1987) finds that, when people can choose to get a kiss from their favorite movie star or enjoy a fancy dinner either immediately or later, they preferred the latter. Similarly, Lovallo and Kahneman (2000) show that gamblers were more inclined to delay learning about their outcome when the potential reward was larger, in order to derive greater savoring value from imagining winning the reward.

However, the delaying principle should be applied with caution because it runs against a few other accounts. First, the waiting period is usually unpleasant, which may result in anxiety and stress (Houston, Bettencourt, & Wenger, 1998; Osuna, 1985). Second, the negative experience during waiting is likely to be transferred to the target consumption, and hence reduce overall satisfaction (e.g., Dellaert & Kahn, 1999). Third, from an economic perspective, waiting decreases the present value of the consumption experience. Fourth, because imagined experience sometimes can substitute for real experience (Morewedge, Huh, & Vosgerau, 2010), the anticipation period may lead to adaptation and thus decrease pleasure from the actual consumption. Adding Interruptions and Slowing Down: Adding Interruptions to a Flow of Consumption and Slowing Down Consumption Can Increase Overall Happiness

Whereas the previous section (“Adding Delays”) deals with the procedure of consuming a single unit, this section is about improving overall happiness in consuming a single stimulus repeatedly (e.g., listening to one’s favorite song 10 times) or a series of similar stimuli (e.g., watching 10 episodes of a TV show), during which people generally experience hedonic adaption, get satiated, and enjoy the stimuli less and less (Frederick & Loewenstein, 1999; Kahneman & Snell, 1992). In these situations, adding interruptions (i.e., introducing “breaks” into the course of consumption) can boost happiness because it gives people time to naturally recover from satiation. Indeed, Nelson and Meyvis (2008) find that adding a short break to when participants were receiving a massage or listening to a pleasant song elevated their overall enjoyment of the period as compared with no interruption. Moreover, adding interruptions can help even when the interruption itself is somewhat negative. For example, Nelson, Meyvis, and Galak (2009) show that TV commercials (i.e., not-so-pleasant distractors) can help “reset” people’s feeling toward the TV program, restore the intensity of the positive experience, and increase overall enjoyment. However, people usually do not foresee the benefit of adding interruptions, and do not choose to break up positive experiences (Nelson & Meyvis, 2008; Nelson, Meyvis, & Galak, 2009).

Relatedly, these findings also suggest that people will benefit from consuming more slowly when repeatedly experiencing similar stimuli, since a slower pace means more and longer inter-consumption intervals. Indeed, Galak, Kruger, and Loewenstein (2012) provide empirical support for this proposition. In one study, they had participants eat six Hershey’s Kisses while watching a 20-min video. In the forced slow rate condition, participants were instructed to eat each of the chocolates when prompted by the computer, and received the prompt every 200 seconds. In the self-paced condition, participants were instructed to eat at a rate that they thought could maximize their overall enjoyment of the Hershey’s Kisses. All of the participants then ate the chocolates and rated their enjoyment of each piece when they finished that piece. At the end of the study, they also rated their overall happiness retrospectively. Results show that, first, participants in the self-paced condition ate faster than those in the forced slow rate condition. Second, more importantly, participants’ enjoyment of each chocolate declined much faster and their enjoyment of the entire eating experience was lower in the self-paced condition than in the forced slow rate condition. These results confirm the hedonic benefit of slowing down, and also suggest that people do not seem to anticipate how fast they may get satiated from repeated consumption, and as a result consume too rapidly when they have control over the consumption pace. Inducing Curiosity: Adding a Curiosity-Induction Period Before Consumption Can Increase Overall Happiness

Curiosity is conceptualized by Loewenstein (1994) as the desire to “close an information gap,” and is a form of “cognitively induced deprivation.” Just like deprivations of sleep, sex and food that lead people to seek restoration, the deprivation of one’s cognitive state can also result in a natural resolution, meaning that the desire to resolve curiosity can be a goal in and of itself, beyond getting practical benefits such as information (Litman, 2005) and entertainment (e.g., gossip; McNamara, 2011). For example, in one study (Hsee & Ruan, 2016), participants saw 10 pens and learned that 5 of them were prank electric-shock pens that would deliver a painful (yet harmless) shock and that 5 of them were regular pens. In one condition the prank electric-shock pens were labeled so no curiosity was evoked, whereas in the other condition the prank electric-shock pens were unknown so curiosity was induced. Participants then, purportedly, entered into a waiting period for another study during which they could click these pens if they would like to. Hsee and Ruan (2016) find that participants clicked more of the pens (and as a result received more unpleasant electric-shocks) in the latter condition. They coined this effect - that curiosity leads people to opt for expectedly negative outcome - the Pandora Effect, which provides evidence that people can get positive hedonic value through curiosity resolution.

It follows that adding a curiosity-induction stage prior to the target consumption period which resolves the curiosity can increase overall happiness. Ruan, Hsee, and Lu (in press) provide empirical support for this possibility. In the study, participants learned that they would read a biography of Einstein. Prior to the reading period, those in the curiosity-inducing condition read 10 questions about the life of Einstein and were prompted to think about the answers, whereas those in the control condition viewed 10 pictures of Einstein and were not prompted to think about anything related to the biography. Participants then rated their experiences in the prior-to-reading period, read the biography, and rated their experience in the reading period too. Ruan, Hsee, and Lu (in press) find that participants were happier in the curiosityinducing condition than those in the control condition during the entire experiment (i.e., the prior-to-reading phase and the reading phase together), and that the greater overall happiness in the curiosity-inducing condition was mainly driven by happiness in the reading period. In other words, while participants obtained greater satisfaction when reading the biography of Einstein after thinking about questions about Einstein (than not), thinking about those questions per se did not decrease their happiness in the first stage. Importantly, people do not seem to be aware of the hedonic benefit of inducing curiosity and do not choose optimally. For example, in another condition, when given a choice between viewing questions about Einstein or pictures of Einstein before they read the biography, participants did not prefer the curiosityinduction method. (Mis)Match Between the Choice Phase and the Consumption Phase

Because people possess malleable (i.e., context-dependent and time-dependent) preferences, if the circumstance under which people choose a consumption option mismatches with the circumstance under which they consume the option, they may choose sub-optimally. Therefore, matching the choice phase with the consumption phase, in terms of people’s visceral state (hot or cold), evaluation mode (joint or separate), timing of choice (simultaneous or sequential), and focus (wide or narrow), can improve happiness.

Hot Versus Cold Visceral States

: People’s Visceral States in the Choice Phase and the Consumption Phase May Differ; Matching the Visceral State in the Choice Phase with That in the Consumption Phase Can Improve Happiness During Consumption

Loewenstein (1996) made the distinction between two visceral states - a “cold” state when people are rested, satiated, sexually unaroused, or intellectually satisfied, and a “hot” state when people are tired, hungry, sexually aroused, or intellectually curious. Individuals in one state usually cannot accurately anticipate or predict their preferences and experiences in the opposite state, experiencing an empathy gap. For example, a person who just had dinner will have difficulty simulating how hungry she would feel the next morning.

People’s visceral states change over time. Therefore, when choosing for future consumption too early in advance, people may experience a mismatch in visceral states between the choice phase and the consumption phase. Yet, people tend to project their current state to estimate their future state, exhibiting the projection bias (Loewenstein, O’Donoghue, & Rabin, 2003; see also Loewenstein, 1996; Van Boven, Dunning, & Loewenstein, 2000; Van Boven & Loewenstein, 2003), and choose accordingly and suboptimally. For example, a grocery shopper who just had dinner may not buy enough for her upcoming breakfast, impairing her satisfaction during breakfast, whereas a grocery shopper who just finished work at 5pm, feeling hungry and thirsty, may add an unplanned dessert item (e.g., a big box of ice cream) to her shopping cart, only to find herself too full to eat anything after dinner (Nisbett & Kanouse, 1969; Gilbert, Gill, & Wilson, 2002; Read & Van Leeuwen, 1998). Similarly, right after visiting an art museum, one may be particularly curious (i.e., intellectually aroused) about the stories behind the artwork and purchase related books or DVDs. However, later she may find the books and DVDs gathering dust on her bookshelves, as her curiosity about the artwork fades. To optimize choice and increase consumption happiness, one should engage in more deliberative projection of his or her future states, or reduce the temporal interval between the choice phase and consumption phase.

Joint Versus Separate Evaluation Modes

: People Are Usually in a Joint Evaluation Mode in the Choice Phase but in a Separate Evaluation Mode in the Consumption Phase; Matching the Evaluation Mode in the Choice Phase with That in the Consumption Phase Can Improve Happiness During Consumption

All decisions and judgments are made in the joint evaluation mode (JE), or the single evaluation mode (SE), or some combination of the two (Hsee, 1996). In the joint evaluation mode, two or more options are juxtaposed together and evaluated comparatively; in the single evaluation mode, each option is presented in isolation and evaluated in an absolute sense, without comparison to alternatives. These two modes can systematically shift people’s attention to different attributes of the options and further influence their evaluations. Specifically, when attributes differ in terms of “evaluability” – that is, the extent to which people can evaluate the value of the attribute when it is presented alone, easy-to-evaluate attributes receive more attention and more decision weight in the single evaluation mode, and difficult-to-evaluate attributes receive more attention and more decision weight in the joint evaluation mode (Hsee, 1996; Hsee, Loewenstein, Blount, & Bazerman, 1999; Hsee & Zhang, 2004). Take 4K TVs, the size of the screens is more difficult to evaluate (since they are all very big) than the aesthetic design. Thus when evaluating different 4K TV models one by one (in the single evaluation mode), people will give more weight to aesthetic design than size, whereas when evaluating these models together (in the joint evaluation mode), people will give more weight to the size dimension, suggesting the possibility of a preference reversal. (Note that the evaluability of an attribute differs across individuals. In general, expertise or familiarity with the attribute will improve its evaluability. For example, although the size of a 4K TV might be a difficultto-evaluate attribute for most consumers, it might be an easy-to-evaluate attribute for Best Buy personnel.)

Importantly, people often make choices in the joint evaluation mode, comparing different options, yet they often consume in the single evaluation mode, experiencing one option only. Because people value difficult-to-evaluate attributes more in the joint evaluation mode and easy-to-evaluate attributes more in the separate evaluation mode, they may make suboptimal choice for consumption. For example, one may spend a large sum of money to obtain the bigger 4K TV, only to find that day-to-day she does not enjoy looking at the TV in the living room. To alleviate the impact of such a mismatch, one should try to adopt the single evaluation mode in the choice phase, evaluating options one by one and forming holistic impressions of each of them. Simultaneous Choices Versus Sequential Consumption: While People Usually Consume Options Sequentially, They May Choose the Options Simultaneously; Minimizing This Mismatch Can Improve Happiness During Consumption

Another mismatch between the choice phase and the consumption phase is that while consumption usually happens sequentially, choices may be made simultaneously (i.e., choosing for multiple future consumption episodes). A huge body of literature shows that people are subject to the “diversification bias” that they over-diversify their consumption portfolio when making combined choices for multiple future consumption occasions (Read, Antonides, van den Ouden & Trienekens, 2001; Read & Loewenstein, 1995). For instance, in one study (Simonson, 1990), participants chose three yogurts to eat on three consecutive days in the upcoming week, either in advance (simultaneous choice), or right before each consumption (sequential choice). Those in the simultaneous choice condition incorporated more variety of flavors, including flavors they did not like that much, than those in the sequential choice condition. However, when it came to the consumption period, those in the simultaneous choice condition found themselves having to consume some less-preferred flavors and felt less happy than those in the sequential choice condition who stuck more to their favorite flavor.

This effect is accounted for mainly by three psychological mechanisms (Read & Loewenstein, 1995; Simonson, 1990). The first one is related to the perception of future time – people subjectively contract the interval between future consumption occasions, and thus overestimate satiation. Second, people possess the heuristic that a choice portfolio should incorporate variety and simultaneous choice facilitates the construction of a choice portfolio. Third, because people are uncertain about their future preferences, selecting more variety is a safer choice.

To alleviate the impact of this mismatch, one may deliberately reduce variety when making simultaneous choices, applying a choose-my-favorite rule, or make choices in a sequential manner. Note that the impact of this mismatch can be mitigated if in the consumption stage, the interval between consumption episodes is short, to the extent that the perceived interval and objective interval match. Narrow Versus Wide Focus: People Tend to Fix Their Attention to the Focal Event in the Choice Phase but Even Out Their Attention to Both the Focal Event and Contextual Events in the Consumption Phase; Minimizing This Mismatch Can Improve Happiness During Consumption

When predicting future experiences, people tend to narrowly focus on the target stimuli and ignore the impact of contextual factors, such as ambient environment, mood fluctuations, and other life events. Consequently, this focalism bias leads people to overestimate both the intensity and the duration of the focal stimuli’s impact (i.e., the impact bias; Gilbert, Pinel, Wilson, Blumberg, & Wheatley, 1998; Wilson, Wheatley, Meyers, Gilbert, & Axsom, 2000; Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). For example, college football fans thought the victory of their favorite team would make them happier and feel happy for a longer time than it actually did.

In the context of making choices for future consumption, the mismatch of attention span between the choice phase and the consumption phase may lead people to overvalue the focal option in the choice phase, resulting in regret and dissatisfaction in the consumption phase. For example, when a new iPhone comes out, one may be drawn to the new or better features it offers (e.g., a faster chip, a more sensitive 3D touch system, a brighter and more clear screen with retina display), overestimate its hedonic impact in one’s daily life, and willingly pay a high price to purchase the new iPhone. However, once she owns the new iPhone, the phone will gradually lose its attentional prominence, because it will become one of many things – such as mundane activities (e.g., laundry), work duties, and environmental factors (e.g., good or bad weather) – that influence her overall happiness. As a result, this consumer may feel unsatisfied and regret the purchase. To alleviate the impact of this mismatch, one may deliberatively widen the span of focus in the choice phase, for instance, by actively considering other factors that may contribute to his/her future happiness, in order to make a more accurate estimation of the hedonic impact of the target option.

Type of Consumption

Different types of consumption produce different intensity and durability of happiness. Compared with material consumption and consumption that satisfies one’s learned preference (i.e., preferences that are formed recently), experiential consumption and consumption that satisfies one’s inherent preference (i.e., preferences that are formed early in evolution), respectively, generate greater happiness and longerlasting happiness. Experiential Versus Material Consumption: Experiential Consumption Generates Greater and More Durable Happiness Than Material Consumption of Equivalent Monetary Value

In their seminal research, Van Boven and Gilovich (2003) defined material consumption as “spending money with the primary intention of acquiring a material possession – a tangible object that you obtain and keep in your possession” and experiential consumption as “spending money with the primary intention of acquiring a life experience – an event or series of events that you personally encounter or live through.” Research generally finds that compared with material consumption, experiential consumption generates more intensive happiness and more durable happiness. For example, in terms of the intensity of happiness, in one study (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003), participants recalled either a most recent material purchase or experiential purchase of similar price, and rated the enjoyment that purchase brought to them. Results show that experiential purchases generated greater enjoyment than material purchases. In terms of the durability of happiness, in one study (Nicolao, Irwin, & Goodman, 2009), participants made a purchase either from a set of experiential options (e.g., watching videos, listening to songs, playing video games) or from a set of material options (e.g., a ruler, a keychain, a picture frame) that were all priced the same in the lab. Researchers tracked participants’ happiness with their purchases for an extended period of time and found that their happiness declined more slowly in the experience purchase condition than in the material purchase condition, suggesting that happiness engendered by experiential purchase is more resistant to hedonic adaptation.

The different hedonic impacts of experiential and material consumption have three major psychological underpinnings. First, experiential consumption is more important to one’s identity than material consumption; specifically, it constitutes a larger proportion of one’s identity, and is also more central to one’s identity. After all, “we are what we do, not what we have.” Carter and Gilovich (2012) offered a straightforward test of this notion by asking participants to first list five most significant experiential purchases and five most significant material purchases they had made in their lives, and then write a summary of their “life story” in which they could incorporate their significant purchases. Results show that participants weaved their experiential purchases into the life story more often than their material purchases, suggesting that experiential consumption contributes more to one’s identity. Besides, when asked to draw a large circle to represent the self and a few small circles to represent their material and experiential consumptions, participants draw the circles that represent experiential consumption, rather than material consumption, closer to the circle that represents the self, suggesting that people view their experiential consumption as more central to their personal identity. Second, people are less likely to engage in potentially invidious alternative-wise comparison and social comparison after making experiential than material purchases (Carter & Gilovich, 2010; Howell & Hill, 2009). This is because (a) experiences are more inherently evaluable which makes comparison unnecessary (Carter & Gilovich, 2010) and (b) experiences have a lot more variation among experiencers than material possessions have among owners which makes comparisons difficult (Van Boven, 2005). The third reason experiential consumption is more satisfying than material consumption lies in its greater value in enhancing social relationships. Specifically, experiential consumptions are more often shared with others than enjoyed alone (Caprariello & Reis, 2013), making it inherently more social. Besides, experiential consumptions are better conversation topics and people like a conversation partner that talks about experiences more (Van Boven, Campbell, & Gilovich, 2010). Inherent Versus Learned Preferences: Consumption That Satisfies Inherent Preference (i.e., preferences that are formed early in evolution) Produces Longer-Lasting Happiness than Consumption That Satisfies Learned Preferences (i.e., preferences acquired more recently)

Preferences can be categorized by the timing of its formation in human evolution — a million years ago, a millennium ago, or a year ago (Tu & Hsee, 2016). Preferences that formed earlier in evolution are inherent. Examples include our preference for a warm ambient temperature (e.g., 70 °F) over a cold ambient temperature (e.g., 40 °F), for high calorie food (e.g., French fries) over low calorie food (e.g., kale salad), for a good night’s sleep over sleep deprivation, and for being socially accepted over being socially excluded. These preferences are related to our basic biological and psychological needs, are hard-wired, and persist regardless of time and contexts. Preferences that formed later in evolution are learned. Examples include our preference for genuine diamonds over synthetic diamonds, for a $3000 Gucci bag over a $300 Coach bag, for French wine over Californian wine, and for Crocs’ hole-filled shoes over normal looking shoes. These preferences are malleable and vary with time and contexts. Whether a preference is an inherent preference (IP) or a learned preference (LP) falls on a continuum, but for ease of exposition, we treat it as categorical here.

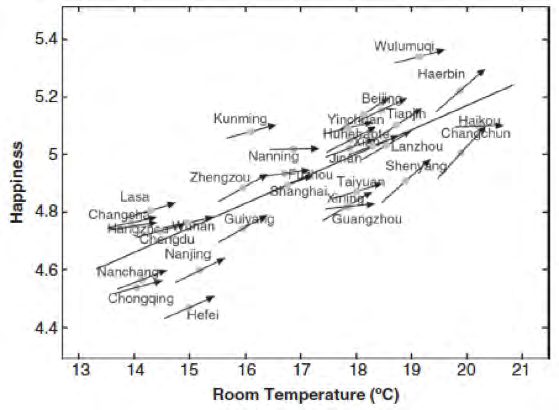

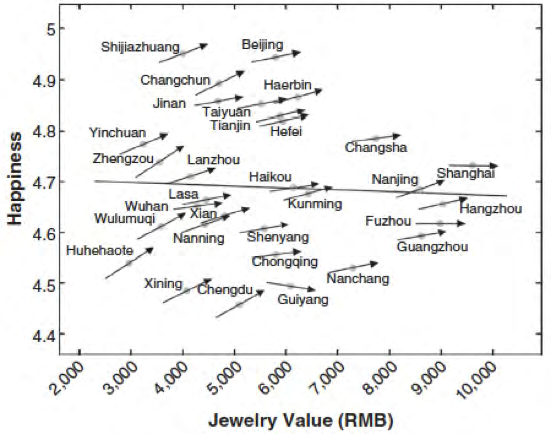

Based on this distinction, Tu and Hsee (2016) proposed that happiness derived from IP attributes needs no social comparisons and is absolute, whereas happiness derived from LP attributes requires social comparison and is relative. Therefore, an improvement on an IP attribute will always increase happiness, whereas an improvement on an LP attribute does not necessarily increase happiness. A field study that compares happiness derived from ambient temperature in winter (a representative IP attribute) and happiness derived from the value of jewelry one owns (a representative LP attribute) within and across 31 major cities in China lent support to this proposition (Hsee, Yang, Li, & Shen, 2009). Specifically, researchers interviewed residents in these cities via phone and collected their answers to four questions: (1) their present room temperature, (2) how happy they are with their present room temperature, (3) the value of their jewelry, and (4) how happy they are with their jewelry. Because social comparison is more likely to happen among people within the same city than between different cities, the researchers compared the impacts of temperature value and jewelry value on happiness both within cities and across cities. Results show that, for room temperature, within each city people with higher room temperature were happier (within-city effect), and between cities people with higher room temperature were also happier (betweencities effect) (see Figure 1). However, for jewelry value, there was only a within-city effect (see Figure 2). These results suggest that happiness derived from room temperature, an inherent-preference attribute, increases as the value of this attribute increases; whereas happiness derived from jewelry value, a learnedpreference attribute, only increases when the value of this attribute is higher relative to the values other people have.

The slope of each small line indicates the effect of temperature within a particular city, and the slope of the long (trend) line indicates the effect of temperature across all the cities. As the graph shows, temperature has a positive effect within most cities (within-city effects), and also a positive effect across cities (between-city effect). Figure 2. The impact of jewelry value on happiness within cities and across cities. The slope of each small line indicates the effect of jewelry value within a particular city, and the slope of the long (trend) line indicates the effect of jewelry value across all the cities. As the graph shows, jewelry value has a positive effect within most cities (within-city effects), but does not have a positive effect across cities (between-city effect).

The second proposition based on this distinction is that the durability of happiness derived from IP and LP will differ. Because inherent preferences have a stable and hard-wired internal reference scale, an improvement on an IP attribute will likely to be permanent and long-lasting. On the contrary, because learned preferences do not have a stable reference scale and rely on external reference points (e.g., other people’s status, one’s past status), an improvement on an LP attribute will likely disappear once the external reference points lose salience in one’s mind or change. For instance, while the increase in wellbeing when a person gets social acceptance will endure regardless of whether other people get socially accepted, the increase in wellbeing via getting a luxury bag will fade when other people catch up or when one forgets the experience of not owning one in the past.

Two empirical studies by us (Tu, Hsee, & Li, 2017) lend support to this hypothesis. In both studies, participants first learned the definitions and examples of IP and LP and then passed a comprehension test before answering further questions. (While IP and LP fall on a continuum, we created comprehension questions in relatively obvious contexts. For example, we asked participants to indicate whether “the preference for a warm ambient temperature to a cold ambient temperature in winter” or “the preference for earning $100,000 a year to earning $80,000 a year” is more inherent. The former is the correct answer. We find that the correction rates are generally high, suggesting that people can intuit and identify the distinction between IP and LP. This approach is similar to what was used in studying material and experiential consumption (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003)). In one study, we asked participants to think about a purchase made with the intention of satisfying an inherent or learned preference. We specified the time frame (“more than two years ago”), the cost (“between $50-$500”), and the durability of the purchase (“something you still have and are still using”). Participants recalled such a purchase, described the type of preference they tried to satisfy, and then rated their immediate happiness and current happiness due to the purchase. We find that, although happiness derived from both types of purchases decreased over time, the decline is greater for the LP-oriented purchase than the IP-oriented purchase. In another study, we replicated this effect in the context of life events, and controlled for immediate happiness. Specifically, we asked participants to recall two improvements in their life within the past 5 years, one satisfying an inherent preference and the other a learned preference. We specified that these two improvements must have had similar immediate impacts on their happiness. Participants described two such improvements and rated whether the improvements had a long-lasting effect on happiness. Supporting our prediction, participants rated improvements that satisfied an inherent preference as having a longer-lasting effect on happiness than those that satisfied a learned preference.

Together, we aim to make two related contributions in conducting this program of research (Hsee et al., 2009; Tu & Hsee, 2016; Tu, Hsee, & Li, 2017). First, we draw a distinction between inherent preferences and learned preferences, a distinction that has potentially profound implications for both theory building and policymaking. Second, we provide empirical evidence suggesting that improvements related to inherent preferences produce more sustainable gains in happiness than do improvements related to learned preferences. This insight is important, in light of the fact that most improvements that have been made over the years are only about learned preferences and not about inherent preferences.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we review research on hedonomics. We present a representative, but not comprehensive, list of determinants of happiness, mainly drawing upon research on judgment and decision making. These factors are subtle but can significantly influence happiness. More importantly, they offer implications for “choice architects” – government, companies, and individual consumers– to design better consumption pattern and procedure, to offer proper timing of choice and consumption, to produce and stimulate the right type of consumption experiences, and ultimately, to improve daily happiness without significantly increasing the possession or consumption of external materials.

Tables & figures

References

- Caprariello, P. A., & Reis, H. T. (2013). To do or to have, or to share? Valuing experiences over material possessions depends on the involvement of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 199–215.

- Carter, T. J., & Gilovich, T. (2010). The relative relativity of material and experiential purchases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(1), 146–159.

- Carter, T. J., & Gilovich, T. (2012). I am what I do, not what I have: The differential centrality of experiential and material purchases to the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1304–1317.

- Clark, A.E. (1999). Are wages habit-forming? Evidence from micro-data. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 39(2), 179-200.

- Dellaert, B. G., & Kahn, B. E. (1999). How tolerable is delay?: Consumers’ evaluations of internet web sites after waiting. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 13(1), 41-54.

- Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 199-169.

- Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In E. Diener & E. Shu (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 185-218). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–13.

- Frederick, S., & Loewenstein, G. F. (1999). Hedonic adaptation. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 302–329). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 351–401.

- Galak, J., Kruger, J., & Loewenstein, G. (2012). Slow down! Insensitivity to rate of consumption leads to avoidable satiation. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5) , 993-1009.

- Gilbert, D.T. (2006). Stumbling on happiness. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Gilbert, D. T., Gill, M. J., & Wilson, T. D. (2002). The future is now: Temporal correction in affective forecasting. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 88(1) , 430–444.

- Gilbert, D. T., Pinel, E. C., Wilson, T. D., Blumberg, S. J., & Wheatley, T. P. (1998). Immune neglect: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3) , 617638.

- Houston, M. B., Bettencourt, L. A., & Wenger, S. (1998). The relationship between waiting in a service queue and evaluations of service quality: A field theory perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 15(8) , 735753.

- Howell, R. T., & Hill, G. (2009). The mediators of experiential purchases: Determining the impact of psychological needs satisfaction and social comparison. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 511– 522.

- Hsee, C. K. (1996). The evaluability hypothesis: An explanation for preference-reversal between joint and separate evaluations of alternatives. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67(3), 247– 257.

- Hsee, C.K., & Abelson, R.P. (1991). Velocity relation: Satisfaction as a function of the first derivative of outcome over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 341–347.

- Hsee, C. K., Hastie, R., & Chen, J. (2008). Hedonomics: Bridging decision research with happiness research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(3), 224-243.

- Hsee, C. K., Loewenstein, G. F., Blount, S., & Bazerman M. H. (1999). Preference-reversals between joint and separate evaluations of options: A review and theoretical analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(5), 576–591.

- Hsee, C. K., & Ruan, B. (2016). The Pandora effect: The power and peril of curiosity. Psychological Science, 27(5), 659-666.

- Hsee, C. K., Salovey, P., & Abelson, R. P. (1994). The quasi-acceleration relation: Satisfaction as a function of the change of velocity of outcome over time. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 30(1), 96-111.

- Hsee, C. K., Yang, Y., Li, N., & Shen, L. (2009). Wealth, warmth, and well-being: Whether happiness is relative or absolute depends on whether it is about money, acquisition, or consumption. Journal of Marketing Research, 46(3), 396-409.

- Hsee, C. K. & Zhang, J. (2004). Distinction bias: Misprediction and mischoice due to joint evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(5), 680–695.

- Huppert, F., Baylis, N., & Keverne, B. (2005). The science of well-being. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3-25). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional wellbeing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489-16493.

- Kahneman, D., & Snell, J. (1992). Predicting a changing taste: Do people know what they will like? Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 5(3), 187–200.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

- Litman, J. (2005). Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: Wanting and liking new information. Cognition & Emotion, 19(6), 793-814.

- Loewenstein, G. (1987). Anticipation and the valuation of delayed consumption. The Economic Journal, 97(387), 668–684.

- Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 75-98.

- Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65(3), 272-292.

- Loewenstein, G., O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2003). Projection bias in predicting future utility. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1209–1248.

- Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (1993). Preferences for sequences of outcomes. Psychological Review, 100(1), 91–108.

- Lovallo, D., & Kahneman, D. (2000). Living with uncertainty: Attractiveness and resolution timing. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13(2), 179-190.

- Lucas, R. E., & Schimmack, U. (2009). Income and well-being: How big is the gap between the rich and the poor? Journal of Research in Personality, 43(1), 75-78.

- McNamara, K. (2011). The paparazzi industry and new media: The evolving production and consumption of celebrity news and gossip websites. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 14(5), 515–530.

- Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938.

- Morewedge, C. K., Huh, Y. E., & Vosgerau, J. (2010). Thought for food: Imagined consumption reduces actual consumption. Science, 330(6010), 1530-1533.

- Nelson, L. D., & Meyvis, T. (2008). Interrupted consumption: Disrupting adaptation to hedonic experiences. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 654-664.

- Nelson, L. D., Meyvis, T., & Galak, J. (2009). Enhancing the television-viewing experience through commercial interruptions. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(2), 160-172.

- Nicolao, L., Irwin, J. R., & Goodman, J. K. (2009). Happiness for sale: Do experiential purchases make consumers happier than material purchases? Journal of Consumer Research, 36(2), 188–198.

- Nisbett, R. E., & Kanouse, D. E. (1969). Obesity, food deprivation, and supermarket shopping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 12(4), 289–294.

- Nowlis, S. M., Mandel, N., & McCabe, D. B. (2004). The effect of a delay between choice and consumption on consumption enjoyment. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(3), 502-510.

- Osuna, E. E. (1985). The psychological cost of waiting. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 29(1), 82105.

- Prelec, D., & Loewenstein, G. (1998). The red and the black: Mental accounting of savings and debt. Marketing Science, 17(1), 4-28.

- Read, D., Antonides, G., Van den Ouden, L., & Trienekens, H. (2001). Which is better: simultaneous or sequential choice? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 84(1), 54-70.

- Read, D., & Loewenstein, G. (1995). Diversification bias: Explaining the discrepancy in variety seeking between combined and separated choices. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 1(1), 34-49.

- Read, D., & van Leeuwen, B. (1998). Predicting hunger: The effects of appetite and delay on choice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 76(2), 189–205.

- Redden, J. P. (2007). Reducing satiation: The role of categorization level. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(5), 624-634.

- Ruan, B., Hsee, C. K., & Lu, Z. Y. (in press). The teasing effect: An underappreciated benefit of creating and resolving an uncertainty. Journal of Marketing Research.

- Seligman, M.E.P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

- Seligman, M.E.P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

- Shen, L. & Hsee, C. K. (2017). Numerical nudging: Using an accelerating score to enhance performance. Psychological Science, 28(8), 1077-1086.

- Simonson, I. (1990). The effect of purchase quantity and timing on variety-seeking behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(2), 150-162.

- Thaler, R.H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(3), 199–214.

- Tu, Y., & Hsee, C. K. (2016). Consumer happiness derived from inherent preferences versus learned preferences. Current Opinion in Psychology, 10, 83-88.

- Tu, Y., Hsee, C. K., & Li, X. (2017). Satisfying inherent preferences to promote sustainable happiness. In P. Moreau, & S. Puntoni (Eds.), NA - Advances in Consumer Research (44). Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research. Van Boven, L. (2005). Experientialism, materialism, and the pursuit of happiness. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 132–142. Van Boven, L., Campbell, M. C., & Gilovich, T. (2010). Stigmatizing materialism: On stereotypes and impressions of materialistic and experiential pursuits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(4), 551–563. Van Boven, L., Dunning, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2000). Egocentric empathy gaps between owners and buyers: Misperceptions of the endowment effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 66– 76. Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1193–1202. Van Boven, L, & Loewenstein, G. (2003). Social projection of transient drive states. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(9), 1159–1168.

- Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2003). Affective forecasting. In M. P. Zanna (Ed), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 35, pp. 345-411). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Wilson, T. D., Wheatley, T., Meyers, J., Gilbert, D. T., & Axsom, D. (2000). Focalism: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 821–836.